At the time of the battle, the war was going well for the French.

They posed a real threat to Vienna, the capital of the Austria and heart of the Grand Alliance that had been formed against them.

John Churchill, the duke of Marlborough, who led an army operating near the Dutch republic, was itching for a great battle.

He decided to intercept the French.

The Dutch were unwilling to let him march south and leave their borders vulnerable,

but Marlborough deceived them by pretending to move no further than the Moselle.

Instead he marched all the way to the Danube, luring the French general Villeroi after him, away from the Netherlands.

The French kept guessing at Marlborough's objective, partly chasing him and strengthening Alsace against a possible attack.

Only when the duke approached Vienna did they realize what he was up to.

Marlborough linked up with prince Eugene of Savoy, commander of the Austrian army.

When the French did not react immediately, he ravaged the Bavarian countryside, which caused him derision.

This prompted Maximilian II Emanuel, the elector of Bavaria, ally of the French, to send many of his troops off to protect his castles.

Not long after Camille, comte de Tallard, arrived on the scene with the French army, strengthened by the Bavarians who re-assembled.

At some 55,000 men his force was slightly larger than that of Marlborough and Eugene and also more experienced.

To him it seemed like Marlborough had overplayed his hand and was ready to receive a beating.

The duke decided to stake everything on an offensive battle, which was risky, as his march had been.

Eugene and Marlborough maneuvered separately but in agreement, luring the French to the plain near Blenheim.

The first deployments started in the darkness and fog of early morning.

Tallard had expected the allies to withdraw to Nördlingen, but when daylight revealed the enemy, he quickly drew his troops up in battle order.

Due to difficult terrain, some of the allied units reached their positions late and others who had arrived earlier had to endure French cannon fire.

Meanwhile engineers furiously built bridges over the small Nebel stream and its surrounding marshy ground, which lay between the armies.

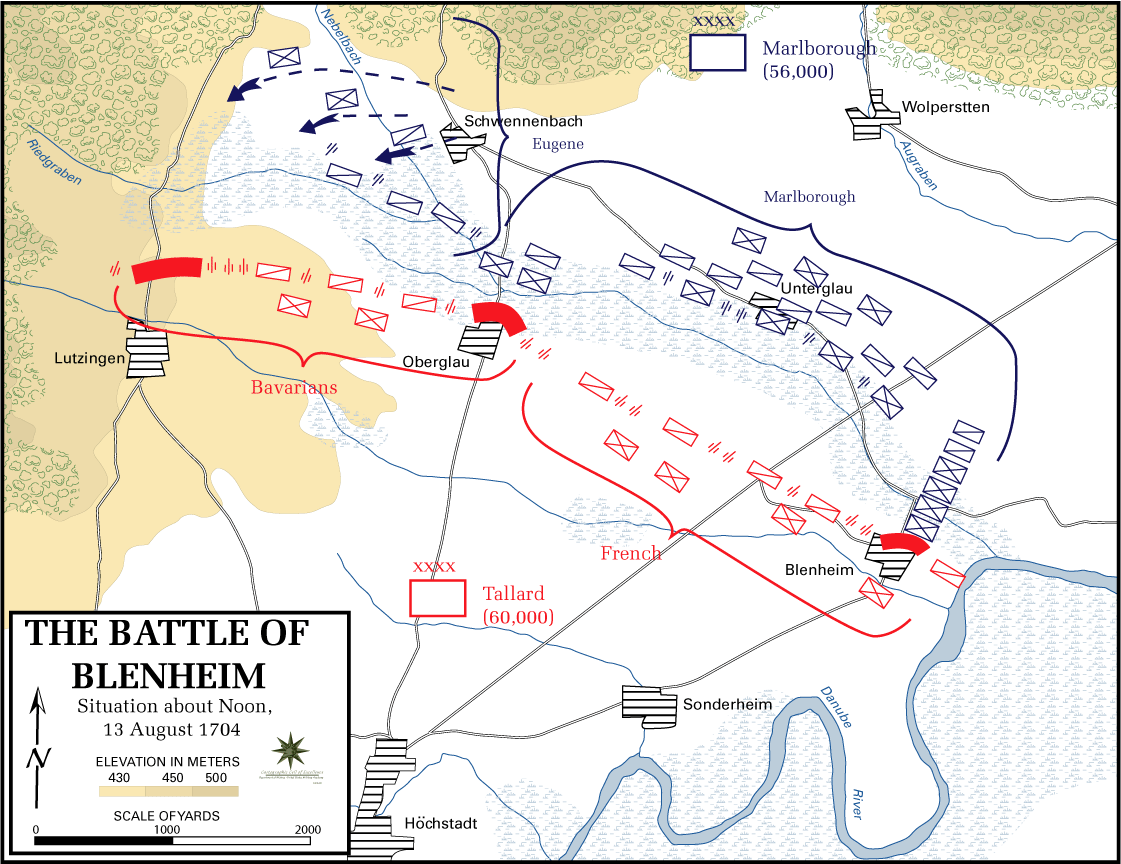

Around 1 P.M. both sides were finally arranged, along a 6 kilometer wide front.

The first attacks were made by the English at the village of Blenheim on their left flank.

They failed to break the French, but caused some panic and drew in substantial French reserves, weakening the latter's center.

On the other flank, Eugene with Prussian and Danish infantry captured Lutzingen with difficulty, suffering heavily from Bavarian artillery fire.

However the cavalry did not manage to provide support and they fell back in disarray, nearly routing.

In the center the fighting was heavy and for several hours neither side gained a significant advantage, though the French cavalry suffered heavily.

They tried to break through at the village of Oberglau to cut the enemy forces in two.

That could have meant the end for the allied army, but its commanders mounted well-directed counterattacks and repulsed the French offensive.

After a brief pause, around 5 P.M. the allies attacked once more between Oberglau and Blenheim.

The French cavalry, already battered, was soon driven off and next the then isolated infantry was broken.

Tallard tried to rally his troops but was captured.

Many fleeing infantrymen drowned in the Danube, others were murdered by aggravated farmers whom they had terrorized in the days before the battle.

Soon after Lutzingen was captured too, however the French in Blenheim continued to resist stubbornly.

Marlborough wanted to rest until the next day, but his brother advised him to tackle the village before the French would break out.

When their commander deserted them and they were surrounded on three sides, they finally broke too and surrendered.

The fighting lasted until 9 P.M., well after dark.

The French lost the battle by overconfidence, placing too much emphasis on the flanks and failing to react to the course of the battle.

The allies won it by working well together, both among generals and the troops using combined arms tactics.

They suffered 4,500 dead and 8,000 wounded; the French 20,000 killed, wounded, drowned or lost and 10,000 - 15,0000 captured.

The battle did not end French power, but seriously dented it and prevented French domination over central Europe

- that did not come until Napoléon.

War Matrix - Battle of Blenheim

Age of Reason 1620 CE - 1750 CE, Battles and sieges